I just heard the terrible news that Mahmoud Darwish passed away. As for many of you, I’m sure, the anguish and pain brought about by this loss is nearly unbearable.Some of us had the privilege, only a few weeks ago, of listening to him reading his poems in an arena in Arles.

I just heard the terrible news that Mahmoud Darwish passed away. As for many of you, I’m sure, the anguish and pain brought about by this loss is nearly unbearable.Some of us had the privilege, only a few weeks ago, of listening to him reading his poems in an arena in Arles.

The sun was setting, there was a soundless wind in the trees and from the neighbouring streets we could hear the voices of children playing. And for hours we sat on the ancient stone seats, spellbound by the depth and the beauty of this poetry. Was it about Palestine? Was it about his people dying, the darkening sky, the intimate relationships with those on the other side of the wall, ’soldier’ and ‘guest’, exile and love, the return to what is no longer there, the memory of orchards, the dreams of freedom…? Yes - like a deep stream all of these themes were there, of course they so constantly informed his verses; but it was also about olives and figs and a horse against the skyline and the feel of cloth and the mystery of the colour of a flower and the eyes of a beloved and the imagination of a child and the hands of a grandfather.

Gently, repeatedly, terribly, by implication, mockingly, even longingly - death. Many of us were petrified. Maybe we sensed - remember Leila? - that this was like saying goodbye. Like this? On foreign soil? Time stopped there, and the lament was made nearly joyous in the ageless rhythm of the two brothers in black on their string instruments accompanying the words coming to us from the earth and from a light blowing over that distant land. We wanted to weep, and yet there was laughter and he made it easy for us and it became festive.

Afterwards, I remember, we did not want to leave the place. Light had fallen but we lingered, embracing and holding one another. Strangers looked each other in the eye, fumbled for a few words to exchange, some thoughts. How awkward it has become to be moved! I remember thinking how deeply he touched us, how generous he was. And how light. Maybe, had he known, he would have wanted to take leave in this way. No drama. No histrionics. No demagogic declarations. Maybe not even much certainty anymore. Despair, yes - and laughter. The dignity and the humbleness of the combatant. And somehow, without us knowing or understanding, his wanting to comfort us. He said he was stripping his verses of everything but the poetry. He was reaching out even more profoundly than he’d ever done before for the universally shared fate and sense of being human. Perhaps he was trying to convey that it was now time to “remember to die.”

The next day when we left, when we said goodbye in that Hotel Nord-Pinus with its huge posters of corridas and the photos of bullfighters fragile like angels in the intimacy of preparing for walking out into the blinding light, with the sweet smell of death lilies in

the foyer, I wanted to kiss his hands and he refused.

Time will pass. There will be eulogies and homages. He will be ‘official’, a ‘voice of the people’… He knew all of that and he accepted it, and sometimes he gently mocked the hyperbole and the impossible expectations. Maybe the anger will be forgotten. Maybe even, the politicians will refrain from trying to steal the light of his complex legacy, his questioning and his doubts, and perhaps some cynics - abroad as well - will, this time, not disgust us with the spectacle of their crocodile tears.

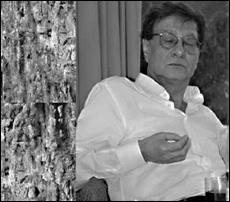

Mahmoud is gone. The exile is over. He will not have lived to see the end of the suffering of his people - the mothers and the sons and the children who cannot know why they should be born into the horror of this life, the arbitrary cruelty of their dying. He will not fade away. Not the silhouette in its dapper outdated clothes and polished loafers, not the intelligent eyes behind the thick lenses, not the teasing, not the curiosity about the world and the intimacy of his reaching out to those close to him, not the sharp analyses of the foibles and the folly of politics, not the humanism, not the good drinking and the many cigarettes, not the hospitality of never imposing his pain on you, not the voice that spoke from the ageless spaces of poetry, not the verses, not the verses, not the timeless love-making of his words.

I just wanted to reach out to you. Some of you, I know, must be crying as I am now, and some never met him; but, surely, for all of us he was a reference. Maybe we will stop somewhere because we hear a flutter of birds overhead, and we will hold a protecting hand to our blinded eyes as we search the sky.

He will be alive for me in that rhythm of birds. I told him in Arles I want to propose to my fellow poets that we should, each one of us, declare ourselves ‘honourary Palestinians.’ He tried to laugh it away with the habitual embarrassment of a brother. And indeed, how puny our attempts to understand and approach the inconsolable must be! We cannot die or write in the place of his people, in the place of Mahmoud Darwish. Still, somehow, however futile the gesture, I need to try and say what an honour it was to have known this man a little and what a privilege and a gift his poetry is. And that I wish to celebrate the dignity and the beauty of his life by sharing this fleeting moment with you.