"The most beautiful of the Nile's birds leaves the lake this evening,” Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti wrote yesterday on Twitter. “Goodbye, Ibrahim Aslan."

"The most beautiful of the Nile's birds leaves the lake this evening,” Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti wrote yesterday on Twitter. “Goodbye, Ibrahim Aslan."

Aslan, one of Egypt’s greatest authors, entered the hospital yesterday with a heart complaint and passed away. He was 77.

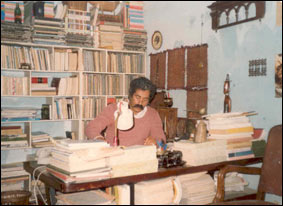

Aslan was born in Tanta in 1935, but his family soon moved to Imbaba, where he spent his formative years and set much of his work. There, Aslan moved through several public and trade schools. His father worked at a post office, and Aslan too worked for a time with Cairo’s mail and telegraph systems.

It was here that the largely self-taught Aslan began to gather much of the material he would later use in his novels and stories. The building blocks of his work were, as he later called it, “the daily debris to which no one pays attention.”

Aslan’s reminiscences, collected in “Something Like That,” address the origins of his creative writing. Aslan was inspired, in part, by Anton Chekhov's humorous short story "The Death of a Government Clerk," in which a clerk accidentally sneezes on a general. Aslan also admitted that he gained a closer view of people’s lives from at least one letter swiped from the undeliverable bin.

At the age of 30, Aslan left the post and telegraph offices behind and began working as a journalist and short-story writer. Compared to his Sixties generation peers, he published relatively little in his forty-seven years of writing. There were three novels, two collections of short stories and two collections of essays. His first novel, “The Heron” (1983), was the best-known and most-celebrated among them. Set against the 1977 bread riots, the novel was lately voted by the Arab Writers Union as one of the 100 best Arabic books of the previous century. It was also made into the well-crafted and popular film, "Kit Kat."

Aslan’s second novel, “Nile Sparrows,” expands on story lines begun in “The Heron,” but was published 16 years later, in 1999. His third and final novel “Two-bedroom Apartment,” appeared in December 2009.

Aslan had a poet’s relationship to language, and one of his literary assets was his great care with words. But at times Aslan also considered this a handicap. He told Mohamed Shoair in 2010, after the publication of his last novel, that, "I think I was a little too afraid of writing."

Aslan told Shoair that he wrote "with an eraser." Other authors paid tribute to this aspect of Aslan’s craft. After hearing of his death, novelist Radwa Ashour tweeted that Aslan’s words were calculated “as though their author were anxious to keep them from harm.”

Elliott Colla, who translated “The Heron,” said, “The world lost a major writer today.” He added that Aslan was not merely a writer, but that he “single-handedly remade the Egyptian novel in a number of ways. [Naguib] Mahfouz insisted that the novel had to be serious, even at the expense of humor, and those who came after Mahfouz accepted this for the most part.” But “Aslan brought the novel back to earth — his characters speak Egyptian, they live banal lives filled with frustration, dead-ends and stalled revolutions — and most of all, they laugh.”

Following his stint in communications, Aslan dedicated the full of his life to writing and editing. He was one of the few Sixties generation authors in Egypt who never joined a political organization. Like the writer-protagonist of “The Heron,” Aslan was in some ways an outsider and an observer. His stories and novels did address the justice he desired, but his activities didn’t draw the attention of Egypt’s police or censors.

So Aslan wrote his books and his newspaper columns, and, in 1997, rose to the position of editor-in-chief of the Afaaq Al-Kitaba (Arab Horizons) book series. There, three years into his editorship, Aslan found himself unexpectedly in the middle of a political firestorm. He and Arab Horizons managing editor Hamdi Abu Golayel had decided to add Syrian author Haidar Haidar's “Banquet for the Seaweed” to the low-cost series. Haidar’s novel, which had been available in Cairo since 1983, was primarily about communism and nationalism. But a few passages about the role of religion attracted the attention of a writer at the Islamist newspaper Al-Shaab.

The biweekly newspaper misrepresented one of Haidar’s sentences and stirred antipathy toward the novel and Aslan. In May 2000, protests erupted. Aslan was called in for an interrogation that reportedly lasted some eight hours, from 10 pm on 10 May to 6 am the following day.

The protests were stifled with tear gas and rubber bullets, but Aslan remained the target of a lawsuit. Less fiery than some, Aslan stated plainly at the time, "It would be very difficult for me to leave Egypt, but I don't want to be imprisoned, either."

In the end, Aslan did not leave Egypt. He continued to live and write in Imbaba, and later in Moqattam. He won a few literary awards, among them a State Incentive Award and a Sawiris Prize — fewer than were merited by his large talent. A number of critics and fans were disappointed that Aslan’s final short novel, “Two-bedroom Apartment,” wasn’t recognized by the International Prize for Arabic Fiction.

Aslan continued to head up the Arab Horizons project through the summer of 2011. Late in the year, he agreed to help reform the "Maktabet al-Osra" (Family Library) project, which had been bogged down by nepotism during the Mubarak era.

Last summer, Aslan told Al-Safir newspaper that “whatever happens next,” he was happy that he had lived to witness the uprisings that began in 2011, which he called “the beginning of the collapse of the barrier of fear.”

almasryalyoum