SCRIPT

When did the ant develop a taste for the news?

When did the ant develop a taste for the news?

Or did it always nurse it within?

Crawling along the newspaper spread

on the floor, it devours each letter

of news, first the big headlines of national mourning

later the medium-sized bride-burning bit

and those who slit each other’s throats

for a dime, and then the small fonts

of suicide, missing persons etc . . .

Thus polishing off each item,

the ant has left.

The paper’s blank now

like the pale cheeks of a pregnant woman

who died for want of blood

Roll it up now and see

the stars at the end of the tube

or place it to your ear and hear

somebody digging a trench somewhere faraway

Place it between your lips

and play the flute

or if you so wish, abandon it

in the bamboo forest nearby

Now the only fear is,

where is the ant

and where is the trail of blood at its feet?

***

AT THE END OF THE VIGIL

The nurse is at the bus stop

Leaving the night-shift behind her

A milk van and a rickshaw pass by

Leaving a whiff of incense

The doc who had come for an emergency

In pyjamas is honking at the exit gate

Those weary after running around

In tunnel dreams are rising sluggishly like statues

On the footpath

Tiffin carriers greet florists

Bicycle bells are calling out

To plastic lotuses in the ponds

The ward boy wielding a long broomstick

Mistakes an orange peel for the fruit

Somebody who unveiled a mosquito net last night

Forgot to remove the nails driven into the sky

The trees convulse

Shaking off the darkness

Let all hospital doors open

Let all children with feverish eyes come into my embrace

Let wounds heal with the mere kiss of a sunray

And let the tears not curdle the milk of our bosoms.

*******************

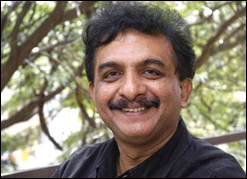

Jayant Kaikini is regarded as one of the most significant of the younger writers in Kannada today. He is a writer of short stories, film scripts and poetry, and is based in Bangalore. His poetry is characterised by subtle imagism, a minute documentation of the seemingly commonplace, a colloquial idiom and a conscientious refusal to engage in any poeticising. He has so far published six anthologies of short stories, four books of poetry, three plays and a collection of essays.

Kaikini was born in Gokarn, an idyllic beach town of coastal Karnataka. His father, Gourish Kaikini, a schoolteacher, was an eminent Kannnada litterateur and mother Shanta, a social worker. After a Masters in Biochemistry from Karnataka University, Dharwad, he moved to Bombay where he worked as a production chemist for 23 years. He shifted to Bangalore in 2000 where he worked as an adviser to a television channel and as an editor of a literary monthly, Bhavana. He is currently active in writing film scripts and hosting television talk shows.

Kaikini received the Karnataka Sahitya Academy award for his first poetry collection at the age of nineteen in 1974. He received the same award again in 1982, 1989 and 1996 for his short story collections. He has been awarded the Dinakar Desai award for his poetry, the B. H. Sridhar award for fiction, as well as the Katha National award and Rujuwathu trust fellowship for his creative writing.

In an introduction to Dots and Lines, an English translation of Kaikini’s short stories, critic C.N. Ramachandran writes, “To understand Jayant’s works, we have to situate him in the literary context of the last two decades of the 20th century. During that period, there arose a group of writers who consciously differed from both the earlier Modernist writers (called Navya in Kannada) and those contemporaneous to them, the Writers of Protest (called Bandaya in Kannada) and Dalit writers. They did not subscribe to any particular philosophical or political system of thinking – be it Existentialism of the Modernists or the Leftist ideologies of the Dalit and Protest writers. On the other hand, what they wished to do was to select precise and authentic details of daily life and organise them in such a way as to culminate in a particular experience . . . Generally, their style was comic-ironic; and the language they used was the spoken language of day-to-day life. They were neither idealists nor cynics; they just wished to observe the life around them – generally mediocre – to register all the fleeting details that marked an ordinary man’s daily routine, and lead up to an experience rich in connotations. Jayant was a major figure in this group of writers who, loosely, can be called ‘post-modernist’.”

The selection of poems in this edition brings to my mind a certain affinity with the work of the late bilingual poet, Arun Kolatkar. There is a similar use of an incisive non-decorative idiom, a keen observation of the singular, the quotidian and the unremarkable, as well as the faith that in an unwavering attention to detail is implicit the larger picture.

Consider the wonderful accumulation of images in ‘Button Rabbit’: the “sour faced tempo”, the cot “in a yogic trance” and the cloth rabbit which provokes a tangential speculation on the life of the humble seamstress who created it. Nothing prepares you, however, for the sudden centripetal movement at the end of the poem when in a miraculous moment of unfettered volition the rabbit breaks free of its glass cage and “leaps out of the tempo into the street/ in search of its creator”. From a household in transit to the existential quest of a toy rabbit – one is carried along by the inexorable logic of the poem. This is the strength of Kaikini’s poetry.

http://www.poetryinternationalweb.net/pi/site/home/index/nl