Recently, Moroccan poet Abdellatif Laâbi was at London’s Mosaic Rooms and Free Word Centre, celebrating the release of his Bottom of the Jar and a new chapbook of his poems. Roland Glasser earlier reported on the launch; now Searle reflects on Laâbi’s poetry and the world map of literary translations.

Recently, Moroccan poet Abdellatif Laâbi was at London’s Mosaic Rooms and Free Word Centre, celebrating the release of his Bottom of the Jar and a new chapbook of his poems. Roland Glasser earlier reported on the launch; now Searle reflects on Laâbi’s poetry and the world map of literary translations.

Let’s imagine a map of ‘world literature’ as the anglophone reader knows it today. All maps are by nature documents of distortion, but I suspect this one would be particularly skewed: similar, perhaps, to a conquistador’s crude atlas, one of those quaintly fanciful affairs where misshapen bodies of land, stretched or shrunk beyond recognition, jostle for space on the page, where monsters crowd the seas and continents curve to fit the edges of the frame. A handful of writers would loom unduly large on this world map, dwarfing their arguably greater, but less anthologized compatriots.

Every port, peak and tributary in Europe would be lovingly charted, though elsewhere major landmarks would go missing. Just as Jerusalem sat squarely at the center of the world on those early maps, so the English-speaking author would dominate this one, leaving other languages to throng the margins with their babble. Whatever Goethe meant when he dreamed of a Weltliteratur, this isn’t it. Instead, we have its anamorphic shadow: a top-heavy world with a bulging center and many unexplored peripheries.

This map would also have to be in perpetual flux, as the anglophone reader’s awareness of foreign literatures shifts over time: new planets swim in and out of his ken in tandem with the vagaries of publishing, translation, literary honors, and the news. A map of inconstancy, then: like the stock exchange, like clouds. In his novel Cloud Atlas, David Mitchell has one character, the young composer Frobisher, deliver this arresting aphorism: “Faith, the least exclusive club on earth, has the craftiest doorman.”

The same could be said of that other broad church we call world literature — a wide-open door guarded by a strict gatekeeper, without whose help you have no hope of crossing the threshold. The gatekeepers here, of course, are translators. On our notional map, well-feted writers such as Orhan Pamuk and Alaa al-Aswany would certainly make the cut, but neither would enjoy such widespread popularity without the efforts and artistry of Maureen Freely or Humphrey Davies in adapting their works for the anglophone palate. And then there are writers who, like the modernist Iraqi poet Badr Shakir al-Sayyab, are revered by their colinguals yet remain virtually unknown outside their own language for lack of decent translations.

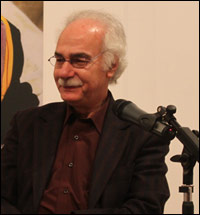

Among the contemporary victims of our map, Abdellatif Laâbi would perhaps be the most glaring omission — an inexplicable blind spot on the English-speaking radar. On a recent evening in February, a small crowd gathered at the Free Word Centre in London to hear Laâbi read from a pamphlet of his poems compiled and translated by André Naffis-Sahely, a young, unplaceable hybrid (Venetian-Iranian, it turns out) and a poet himself. The pamphlet was produced by the Poetry Translation Centre, itself the energetic brainchild of poet and translator Sarah Maguire, who introduced Laabi that night. Focusing on contemporary poetry from Asia, Africa and Latin America, the Centre follows what might be called the Ted Hughes school of translation: working from cribs to establish the literal meaning of a poem, the translators – usually poets themselves – then re-shape these ‘raw’ texts into readable English verse. In this approach, mastery of the source language becomes optional: just as Hughes, who knew only French, produced English versions of Hungarian, Hebrew and Portuguese poetry, so Nick Laird, who is not known for his command of Dari, has ‘translated’ works by Reza Mohammadi, and Mark Ford, whose many talents do not include Arabic, has adapted poems by Al-Saddiq al-Raddi.

Undoubtedly, something is lost in this process – notably, a poem’s verbal texture: its meter, rhythm and rhyme. But with its emphasis on collaboration and on the literary quality of the final poem, the Centre has opened up exciting possibilities for translation, and its many happy outcomes — including Laabi’s dual-language chapbook — are a testament to the method’s success.

Introducing her guest, Maguire was careful to emphasize Laâbi’s renown abroad, citing as evidence his many garlands of recognition, crowned by the Prix Goncourt in 2006. If his name was unfamiliar to the audience in London, it was perhaps, his translator suggested, because anglophone poetry tends to shy away from politics. Whether or not this is true, Laâbi certainly doesn’t: his work is unavoidably, unmistakably political. In Morocco, in 1966, he helped found the iconic magazine Souffles, an explosive blend of poetic experimentalism, political militancy and 1960s counterculture. In the prologue of its inaugural issue, Laâbi wrote that it would be ‘the organ of a new literary and poetic generation’. And so it was, but that breath was soon cut short: six years later the magazine was banned – these were the so-called ‘years of lead’ of Hassan II’s rule – and Laâbi arrested, beaten and sentenced to ten years in jail for ‘crimes of opinion’, a charge his translator described as ‘fabulously vague’. Released in 1980, he fled to France where he continues to live.

With its ten short poems, this chapbook is a regrettably modest sample of Laâbi’s expansive oeuvre. Still, these carefully chosen pieces offer a welcome glimpse into the kaleidoscope of his poetic sensibility, by turns savagely satirical (“The Wolves”), playfully allegorical (“The Poem Tree”), grimly funny (“Dish of the Day”), philosophical (“In Vain I Migrate”), sensual (“Burn the Midnight Oil”) and elegiac (“The Earth Opens and Welcomes You”). Beyond these deft shifts of register, however, the poems all share an essential preoccupation with language, its ambiguities and the possibility of its failure. More, they betray a paradoxical anxiety: beneath their lyrical, richly woven exterior, they are miniature meditations on the limits of poetic expression – indeed, on the ultimate poverty and helplessness of language itself.

“My Mother’s Language” begins with a distant memory (“It’s been twenty years since I last saw my mother”) and ends with the urgency of preserving a fragile legacy (“I am the last man/ who still speaks her language”). The poet becomes a conduit, a translator of sorts, giving voice to the “endangered species” of his mother’s words:

‘it’s as if she were using my mouth

to voice her profanities, curses and gibberish

the invisible litany of her nicknames…’

Here the translator has curiously elided the original metaphor of the rosary: “le chapelet introuvable de ses diminutifs.” It’s a lovely image – a harried, affectionate mother stringing pet names together like prayer beads – yet is blotted out in translation by the more abstract “litany.”

The poem pays bittersweet homage to a mother who “starved herself to death” while her son lay “in the cave/ where convicts read in the dark.”But it really mourns a greater loss, as the quiet filial lament gives way to something graver still: a requiem for a whole language – a way of seeing – threatened with extinction.

Even when they are grave, these poems tread lightly, weightlessly, haunted perhaps by the idea that language, poetic or otherwise, can obstruct as much as it elucidates, or can become a burden to those who receive it. This fear is touched on and allayed in “The Earth Opens and Welcomes You,” a poignant elegy to the Algerian poet Tahar Djaout, who was assassinated by Islamist guerrillas in 1993. One day, Laâbi promises the departed,

‘your children will grow

and read your poems unashamed’

(‘tes enfants grandiront

et liront sans gêne tes poèmes’)

The phrase “sans gêne” could mean several things here, but I’m not sure shame comes into it. It could mean “untroubled,” ”without fear” – that dream of a future relieved of politics – or it could mean “with ease” – that other, equally remote dream of a language universally, seamlessly understood. In reality it means both: the dream of a poetry delivered of its snags and of its liabilities. Like death, the poem promises a general unburdening. Its wild hope is the absolution of language from politics.

Political violence aside, language can also be “endangered” in more subtle ways: when it is corrupted or abused. In “The Manuscript,” an impish Satan hijacks and absconds with the manuscript of a work in progress. The poet complains that “whenever I wrote a word, he immediately added another – with what I must say seemed like a real sense of entitlement.” Here again the poem suffers in translation: “un sens réel de l’à-propos” does not mean “entitlement” at all; in fact, it means the same as “apropos” in English. The implication is that Satan’s poetic trouvailles are unexpectedly apt, promising, inspired. This is darkly funny – the devil is a poet, too! – and also troubling: if both are equally gifted in eloquence, how will we tell the poet’s word from the devil’s? In a scenario typical of Laâbi’s black humour, the poet competes with Satan for the last word and loses to the latter’s cunning. It is a fine poem, light-footed and faintly surreal, but much of the comedy and underlying unease are lost in the English version.

For all its universalizing breadth, Laâbi’s linguistic anxiety is no doubt rooted in the particular frustration of the colonized. In an early issue of Souffles, he lamented the “linguistic infirmity” of the post-independence writer, newly unchained from the language of his colonizers but not yet master of his own. No more anchored to the “endangered species” of his mother tongue than to his children’s easy fluency, he inhabits a painful in-between:

‘In my sleep I speak

a medley of languages

and animal calls’

(the latter phrase somewhat tamer than the original ‘crix d’animaux’).

And yet when, on that recent evening in London, Laabi was asked to explain himself for not writing in Arabic, he smiled patiently and sighed. “J’écris en français,” he simply said. “C’est une question d’histoire.” Similar questions followed, tiresome in their curiosity, their respectful bewilderment (but you are an Arab!), until Laâbi countered with dry panache: “You know, writing in another language is not a capital sin! To live in one culture, to speak only one language, is to live in a prison. And you may have guessed that I don’t much care for prisons.”

Having placated his faintly accusatory audience, Laâbi paid homage to his translator: how lucky he was, he said, to be translated not just by a poet but by one who is similarly many-voiced, bridging several languages and cultures. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Naffis-Sahely’s track record shows a predilection for the hybrid and the hyphenated: besides Laâbi, he has also translated two novels by the Haitian poet and painter Franketienne, who writes in both French and Creole. And at last summer’s Poetry Parnassus, a festival bringing together writers from every competing Olympic nation, he translated a poem by Ribka Sibhatu, who is from Eritrea and writes in Italian.

Naffis-Sahely is that rare thing: a polyglot poet, and undoubtedly a gifted translator. Yet there are moments, at least in this slim volume, where he seems to strip Laâbi’s poetry of its humor and occasionally, more egregiously, of its political bite. Above all, though, he has performed a great service in rendering this singular poet’s voice into English.

On the mappa mundi of world literature, then, Abdellatif Laâbi would not be one of those strange, half-sunken creatures lurking in exotic seas, but rather a terra incognita – a beautiful, undiscovered continent that had simply fallen off the edge.

Yasmine Seale is a writer and translator living in London.

Arablit.wordpress