Kanafani with his beloved niece Lamees; both were killed by a car bomb "almost certainly" set off by the Israeli Mossad.

Kanafani with his beloved niece Lamees; both were killed by a car bomb "almost certainly" set off by the Israeli Mossad.

A number of Ghassan Kanafani’s literary works have been adapted for stage or screen. The Palestinian author’s first novel, Men in the Sun, was made into a film titled al-Makhduun by Egyptian director Tawfiq Salim and banned in some Arab countries for its portrayal of Arab regimes. In 1977, Israeli authorities banned the performance of a theatrical adaptation of Men in the Sun that was set to be staged in Nazareth.

But perhaps no adaptation of Kanafani’s work has stirred as much controversy as the recent Hebrew staging of the novella “Return to Haifa,” its (unauthorized) English-language staging in Chicago, and its upcoming “sur-titled” Hebrew (with a sprinkling of Arabic) performances in Washington, D.C.

An Arabic-language version of the novel also played in Beirut last month. Although well-reviewed, it didn’t seem to make many waves.

To sum up: “Return to Haifa”—which is available in English translation as part of the collection Palestine’s Children—tells the story of a Palestinian couple, Said and Safeyya, driven from their home during the 1948 Nakba and separated from their infant son.

When the couple is allowed to visit their old home in Haifa twenty years later, they return desperate for information about their son, Khaldoun. But Khaldoun doesn’t want to know them: He was adopted by the woman who was given their house. He has been renamed Dov, and is now an officer in the Israeli reserves.

A Hebrew adaptation of “Return to Haifa” was staged in 2008. At the time, some Israelis protested outside of rehearsals. Kanafani is, after all, a difficult figure for many Israelis: He was one of the architects of Palestinian “culture of resistance,” and, as the British paper The Independent puts it, Kanafani “was killed at the age of 36 in Lebanon along with his [seventeen-year-old] niece when his car was blown up – almost certainly by [Israeli] Mossad….”

There are a number of interesting facets to the Hebrew, Arabic, and “rogue” English stagings of Return to Haifa. You can read a critique of the English version in the Examiner. But what interests me here is the endings of the Beirut and Israeli plays.

Let’s start with the text of the novella, translated into English by Barbara Harlow and Karen E. Riley. The novella finishes with Said wishing that his other son, Khalid, had joined the fedayeen, or resistance movement.

Said rose heavily. Only now did he feel tired, that he had lived his life in vain. These feelings gave way to an unexpected sorrow, and he felt himself on the verge of tears. He knew it was a lie, that Khalid hadn’t joined the fidayeen. In fact, he himself was the one who had forbidden it. He’d even gone so far as to threaten to disown Khalid if he defied him and joined the resistance. The few days that had passed since then seemed to him a nightmare that ended in terror. Was it really he who, just a few days ago, threatened to disown his son Khalid? What a strange world! And now, he could find no way to defend himself in the face of this tall young man’s disavowal other than boasting of his fatherhood of Khalid – the Khalid whom he prevented from joining the fidayeen by means of that worthless whip he used to call fatherhood! Who know? Perhaps Khalid had taken advantage of his being here in Haifa to flee. If only he had! What a failure his presence here would turn out to be if he returned and found Khalid waiting at home.

According to The Independent, the main alteration in the Hebrew staging is that:

…while the novella in effect ends bleakly with Said’s declaration that only another war will solve the problem, the play, while retaining the passage, ends with an, albeit uncertain, hint of possible reconciliation between the families. At the very least, says the director [Sinai Peter], the ending is about the need ‘to begin a dialogue.’

The staging in Beirut ends differently. A review of the December 2010 staging in The Daily Star states:

As the lights begin to dim over Haifa, the bride and groom wrap themselves in the keffiyeh – once a purely folkloric garment native to the Levant, now a symbol of the Palestinian resistance – to indicate that the future will be one of armed struggle.

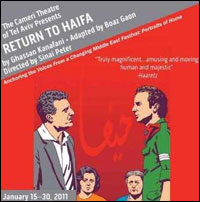

A poster promoting the Hebrew version of the play.

Both stagings, I believe, have been authorized by Kanafani’s widow and thus the “Kanafani estate” (unlike the “rogue” version in Chicago). How would Kanafani have wanted to see his work staged? I suppose, unfortunately, the point is moot.

More from Kanafani:

“Letter from Gaza” by Ghassan Kanafani

“Jaffa: Land of oranges,” by Ghassan Kanafani, translated by Mona Anis and Hala Halim

The estate’s official website; you can find a bit more of his translated work here.

Books in English translation include Men in the Sun and Other Palestinian Stories, translated by Hilary Kilpatrick; Palestine’s Children: Returning to Haifa & Other Stories, translated by Barbara Harlow and Karen E. Riley; and All That’s Left to You, translated by May Jayyusi and Jeremy Reed.

Arabic Literature (in English)