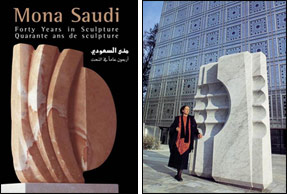

David Tresilian talks to Jordanian sculptor Mona Saudi about Inspirations poétiques, her current Paris show

Visitors to the Institut du monde arabe in Paris have long had the opportunity to admire Jordanian sculptor Mona Saudi's large-scale sculpture, entitled Spiritual Geometry, mounted in the square in front of the building and installed on the occasion of a group show of Arab contemporary artists in 1987. Moreover, Saudi herself is far from being a stranger to the French capital.

Visitors to the Institut du monde arabe in Paris have long had the opportunity to admire Jordanian sculptor Mona Saudi's large-scale sculpture, entitled Spiritual Geometry, mounted in the square in front of the building and installed on the occasion of a group show of Arab contemporary artists in 1987. Moreover, Saudi herself is far from being a stranger to the French capital.

A graduate of the city's prestigious Ecole des beaux-arts, where she studied in the 1960s, Saudi has had frequent exhibitions in Paris since, notably in 1993, when she took part in a group show of the work of contemporary international sculptors, and in 1997 when her work was displayed at the Paris city hall as part of an exhibition of contemporary Jordanian art.

Today, Saudi is back in Paris, this time for an exhibition of her work, both sculpture and graphic pieces inspired by poets St-John Perse and Mahmoud Darwish, at the Europia Gallery in the seventh arrondissement. Running until 24 December at this friendly exhibition space that also organises a variety of cultural events and represents a list of Arab artists, the exhibition, entitled Inspirations poétiques, is Saudi's first Paris show since 2005, when she was invited to present her work in the context of a group show of work by international women artists.

Saudi herself was present for the vernissage, having made the short journey from London, where she had been present at another outing of her work at the Mosaic Rooms, a new exhibition space belonging to the A.M. Qattan Foundation in Kensington.

Speaking to the Weekly at the Paris exhibition, Saudi, now in her sixth decade and internationally one of the best-known Jordanian artists, explained the connections between the graphic and sculptural pieces on show, linked, she said, by a common interest in organic forms and in nature as both source of inspiration and material.

Unlike painting, Saudi said, sculpture does not deal in visual illusion, and making sculpture, which she has been doing for more than 40 years, involves both intellectual and physical effort. Sculpture, unlike painting, confronts the viewer in three dimensions, and it has its own life and material presence.

Making sculpture, Saudi's kind of sculpture, requires a keen appreciation of the physical properties of different kinds of stone. She explains that wherever she finds herself in the world she looks into the specific qualities of the local stone. Sculpture also takes time and physical effort, being an affair of cutting and polishing and a form of manual work that can take months to achieve.

"I don't believe in 'development' in the arts, though it is true that in the 1980s we began to see a different kind of art, conceptual art, that created three-dimensional pieces, call them sculpture, in mixed media. My work is different. It can take months and months of physical effort, physical difficulty, to produce a work, and for this reason it implies a different rhythm of life and production. My work is not commercial -- it cannot be produced or reproduced quickly. Instead, it involves patience and a deep physical involvement with the material. In my career as an artist, I have always aimed to remain true to this kind of work."

Pointing to some of the pieces in the Paris show, Saudi explains that they are made from Jordanian jade, cut and polished into abstract forms. "Stone is local," she says. "It comes from and expresses the earth." Is her choice of Jordanian stone related to her identity as an Arab and Jordanian artist?

While stone may be local, Saudi says, in the sense that it has a local origin and expresses a particular geography, it comes from the earth and does not have a political affiliation. She is an Arab artist, she says, though her inspiration has been western, and she mentions the names of Romanian sculptor Constantin Branscusi and British sculptors Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth, as well as her formation at the Paris Ecole des beaux-arts.

Yet, Branscusi and Moore, she points out, were themselves inspired by non-western forms of sculpture, though their work also emerged from a particular place and time. "In the same way, through working in the footsteps of these masters, and observing their inspiration from non-western forms of art, I have been able to place myself more securely in the heritage of Arab art, knowing better where I come from in the Arab heritage of sculpture in stone."

Saudi's biography makes frequent mention of her involvement in the avant-garde of Arab art, in her work for the cultural review Mawakif, for example, overseen by Syrian poet Adonis, whose editorial board she joined in 1969 when working in Beirut, and her frequent interventions in support of the Palestinian cause. She participated in many collective exhibitions by Arab artists in the 1970s and 80s in support of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation, and the present show bears witness to her close feeling for the work of Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, whose work she began to create illustrations for in the 1970s.

In the autobiographical note that Saudi wrote for this year's London exhibition, she looks back, from the perspective of half a century later, on the young girl who "took long walks through the bare hills of my then very small town, Amman, where our house was surrounded by ancient ruins dating back many millennia, to the age of the Ammonites, the Edomites and the Nabateans, who were all stone carvers."

"I dreamt of traveling to Paris to study art, but my traditional and religious family would never have given me permission, so I left home in secret at the age of 17 and started my life's journey. I spent one year in Beirut, where I frequented poets and artists in a city that was culturally alive with innovations in art and literature in the heady days of the early 1960s... A few sales of my drawings and paintings were enough to buy me a ticket that allowed me to get on a ship and sail across the Mediterranean."

As important, perhaps, as Saudi's involvement in the Arab avant-garde was her work from the early 1980s onwards that began to achieve wider recognition in the form of the commissions she received to produce large-scale site-specific works that would themselves contribute to characterising Arab public space. In 1983, there were the Petra Bank commissions for public spaces in Amman, followed by a commission, the Circle of Seven Days, for the University of Science and Technology in Jordan in 1986, and, of course, the commissioned work for the Institut du monde arabe in Paris later in the decade.

Does she consider her identity as an Arab artist to have assisted or frustrated her international career? There were few young women, fewer still young women of Arab origin, working at the Ecole des beaux-arts in Paris in sculpture in the 1960s. Saudi is adamant that had she not been an Arab her work would have been more sympathetically received by European gallery owners at the time, though she also wryly mentions that some at least took an interest in her because they were looking for work from the holy land. "When they discovered that I was not from the right part, they changed their minds."

Since then, there has been something of a sea-change in international attitudes to work from the Arab world, though Saudi points out that such work is still underrepresented in international public collections, and the Qattan Foundation exhibition, held from September this year, was her first UK show. While Saudi is ready to talk about the apparent "glass ceiling" that can sometimes seem to affect the careers of Arab artists abroad, she seems happier speaking about the provenance of her first love, sculpture.

Learning that she is being interviewed for an Egyptian newspaper, she recounts a visit to the Mahmoud Mokhtar Museum in Cairo, dedicated to the work of the early 20th- century Egyptian sculptor, also a graduate of the Paris Ecole des beaux-arts and responsible for some of Egypt's most important public sculpture, including Egypt's Renaissance near Cairo University. "He was really on the edge of something," Saudi says, "but he died terribly young, at the age of only 35. He didn't live long enough to be able to develop his ideas."

She compares Mokhtar to Iraqi sculptor Jawad Selim, born in 1920 and one of the pioneering figures in the development of modern Iraqi art. Selim studied in Paris and at the Slade School in London, and returning to Baghdad he was appointed professor of sculpture at the Institute of Fine Arts. Like Mokhtar, Selim died young, at only 40 years old, and "he wasn't given the time to work out his ideas," Saudi says, adding that his " Liberty Monument, one of his most important works of public sculpture, can still be seen where it stands in the centre of Baghdad."

Saudi exhibited at the 2003 Cairo Biennale and is always pleased to be able to visit Egypt. Has she thought of exhibiting at the Aswan International Sculpture Symposium? Perhaps it won't be too long before Mona Saudi's work is on show once again in Egypt.

Mona Saudi, Inspirations poétiques, hommage à St-John Perse, Mahmoud Darwish et Camille Claudel, Espace Europia, Paris.