How thrilled is he really about his coming visit to Haifa? What was the impact on him of a report that 1,200 tickets (out of a total of 1,450) for his poetry-reading appearance this Sunday in an auditorium on Mount Carmel had been snatched up in one day?

How thrilled is he really about his coming visit to Haifa? What was the impact on him of a report that 1,200 tickets (out of a total of 1,450) for his poetry-reading appearance this Sunday in an auditorium on Mount Carmel had been snatched up in one day?

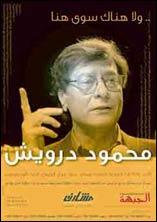

* Does this embrace move Mahmoud Darwish, known as the Palestinian national poet, who in recent years has lived in Amman and occasionally in Ramallah?

"When I passed the age of 50, I learned how to control my emotions," Darwish says, during a conversation that takes place in Ramallah. "I am going to Haifa without any expectations. I have a barrier on my heart. Maybe at the moment of the encounter with the audience a few tears will fall in my heart. I anticipate a warm embrace, but I am also apprehensive that the audience will be disappointed, because I do not intend to read many old poems. I would not want to appear as a patriot or as a hero or as a symbol. I will appear as a modest poet."

* How does one make the transformation from being the symbol of the Palestinian national ethos to being a modest poet?

"The symbol does not exist either in my consciousness or in my imagination. I am making efforts to shatter the demands of the symbol and to be done with this iconic status; to habituate people to treat me as a person who wishes to develop his poetry and the taste of his readers. In Haifa I will be real. What I am. And I will choose poems of a high level."

* Why do you disdain your old poems?

"When a writer declares that his first book is his best, that is bad. I progress successively from book to book. I have not yet decided what I will read to the audience. I am not stupid. I will not disappoint them. I know that many want to hear something old."

Darwish arrived in Ramallah from Amman on Monday morning of this week. He was scheduled to hold working meetings in the days that followed and then go to Haifa, the city in which he embarked on his literary path, in the 1950s. He doesn't yet know how he will travel - there are many volunteers who want to drive him to the meeting in Haifa with residents of the Galilee. The evening is being organized by Siham Daoud, a poetess and editor of the literary journal Masharef, in conjunction with the Hadash Arab-Jewish political party. Darwish will speak and read about 20 of his poems. Samir Jubran will accompany him on the oud and the singer Amal Murkus will moderate. Darwish hopes the Interior Ministry will let him stay in Israel for about a week, although the entry permit he received is valid for only two days.

The conversation with the poet takes place at 4 P.M. in the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center in Ramallah. The magnificent, well-kept building contains an art gallery and a hall for films and concerts. It also has a spacious office, from which Darwish edits the poetry journal Al-Karmel.

The room we are in contains a library rich in Arabic books, though a few Hebrew ones are interspersed among them. There is a poetry collection put out by the Hebrew literary journal Iton 77, Na'ama Shefi's "The Ring of Myths: Israelis, Wagner and the Nazis," as well as copies of the literary-political journal Mita'am, edited by the poet Yitzhak Laor, and a poetry collection by Sami Shalom Chetrit.

Darwish, thinner than ever, elegantly dressed, is cordial. For someone who eight years ago was pronounced clinically dead and was restored to life almost miraculously, he looks fit and younger than his 66 years.

"Is there any hope for this nation?" I ask, and Darwish, the great pessimist, does not even bother asking which nation I am referring to. "Even if there is no hope, we are obliged to invent and create hope. Without hope we are lost. The hope must spring from simple things. From the splendor of nature, from the beauty of life, from their fragility. One may forget the essential things occasionally, if only to keep the mind healthy. It is hard to speak of hope at this time. That would look as if we were ignoring history and the present. As though we were looking at the future in severance from what is happening at this moment. But in order to live we must invent hope by force."

* How do you do that?

"I am a worker of metaphors; not a worker of symbols. I believe in the power of poetry, which gives me reasons to look ahead and identify a glint of light. Poetry can be a real bastard. It distorts. It has the power to transform the unreal into the real, and the real into the imaginary. It has the power to build a world that is at odds with the world in which we live. I see poetry as spiritual medicine. I can create in words what I do not find in reality. It is a tremendous illusion, but a positive one. I have no other tool with which to find meaning for my life or for the life of my nation. It is in my power to bestow on them beauty by means of words and to portray a beautiful world and also to express their situation. I once said that I built with words a homeland for my nation and for myself."

* You once wrote, "This land lays siege to us all," and today more than ever, the feeling of depression and helplessness must be overwhelming.

"The situation today is the worst one could have imagined. The Palestinians are the only nation in the world that feels with certainty that today is better than what the days ahead will hold. Tomorrow always heralds a worse situation. It is not just an existential question. I cannot speak about the Israeli side; that is not my expertise. I can speak only about the Palestinian side. Already in 1993, on the eve of the Oslo agreement, I knew that the agreement held out no promise that we would reach true peace based on independence for the Palestinians and the end of the Israeli occupation. Despite that, I felt that people were experiencing hope. They thought that maybe a bad peace was preferable to a successful war. Those dreams were deceptive. The situation now is worse. Before Oslo there were no checkpoints, the settlements had not expanded like this, and the Palestinians had work in Israel."

* Do you think the readiness for peace was mutual?

"The Israelis complain that the Palestinians do not love them. That is really funny. Peace is made between states and is not based on love. A peace agreement is not a wedding reception. I understand the hatred for the Israelis. Every normal person hates living under occupation. First one makes peace and then one examines feelings like loving or not loving. Sometimes after making peace, there is no love. Love is a private matter and cannot be forced on others."

* What hope are you talking about?

"I accuse the Israeli side of not expressing readiness to end the occupation in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. The Palestinian people is not seeking to liberate Palestine. The Palestinians want to lead a normal life on 22 percent of what they think is their homeland. The Palestinians suggested that a distinction be made between homeland and state, and they understood the historical development that led to the present situation, in which two peoples are living on the same land and in the same country. Despite that readiness, there remained nothing to talk about."

* You mentioned the Gaza Strip. What do you think of the new reality there?

"It is a tragic situation. An atmosphere of civil war. What happened between Fatah people and Hamas people in Gaza reflects a closed horizon. There is no Palestinian state and no Palestinian Authority, and people there are fighting one another over illusions. Each side wants to take control of the government. It's all 'as if' - as if there is a state, as if there is a government, as if there is a minister of this or that, as if there is a flag and as if there is an anthem. A lot of as if, but no content. If and when you put people in prison - and the Gaza Strip is one big prison - and the prisoners are poor and lack everything, unemployed and deprived of basic medical care, you will get people with no hope. That creates a seemingly natural feeling of internal violence. They do not know whom to fight, so they fight each other. That is what is called civil war. It is an explosion amid the mental and economic and political pressures."

* Are you frightened by the rise of Hamas fundamentalism?

"There is a cultural conflict between the secular side, which believes in multiculturalism and a national homeland, and people who look at Palestine exclusively through the prism of the Islamic heritage. It does not frighten me politically. It is frightening culturally. Their inclination to force their principles on everyone is not comfortable. They believe in one-time democracy, and that only to reach the polling booth and gain power. Therefore they are a catastrophe for democracy. It is anti-democratic democracy. But both sides, Fatah and Hamas, cannot remain severed. At the moment, when the blood is hot and the wounds are bleeding, it is hard to talk about a dialogue, but in the end, if Hamas apologizes for what it did in Gaza and rectifies the results of the campaign in Gaza, it will be possible to talk about dialogue. It is impossible to ignore Hamas as a political force that has supporters in Palestinian society."

* So you are again playing into Israel's hands, which profits quite a bit from this situation.

"Israel claimed all along that there was no one to talk to, even when there was someone to talk to. Now they say that it is possible to talk to Mahmoud Abbas, but Abbas was there before Hamas won the elections. What can Abbas do if not one checkpoint has been removed? This is the Israeli policy, which invigorates Palestinian extremism and violence. The Israelis do not want to give anything in return for peace. They do not want to withdraw to the 1967 boundaries, they do not want to talk about the right of return or about the evacuation of settlements, and certainly not about Jerusalem - so what is there to talk about? We are in a deadlock. I do not see an end to this dark tunnel, so long as Israel is unwilling to differentiate between history and legend.

"The Arab states are today ready to recognize Israel and are begging Israel to accept the Arab peace initiative, which speaks of a return to the 1967 boundaries and the establishment of a Palestinian state in return for not only full recognition of Israel but also full normalization of relations. So you tell me who is missing the opportunity. It is always said that the Palestinians never miss an opportunity to miss an opportunity. Why is Israel emulating the rejectionism of the Arabs?"

* Do you think you will live to see any sort of agreement between the two nations?

"I do not despair. I am patient and am waiting for a profound revolution in the consciousness of the Israelis. The Arabs are ready to accept a strong Israel with nuclear arms - all it has to do is open the gates of its fortress and make peace. Stop talking about the prophets and about Rachel's Tomb. This is the 21st century - look what is going on in the world. Everything has changed, apart from the Israeli position, which as I said links history with legend."

* The terrible association between land and death is now almost taken for granted by both sides.

"I said that a cultural revolution is needed by the politicians in Israel in order to understand that it is impossible to ask the young people in Israel to wait for the next war. Globalization is affecting the young; they want to travel and live and build a life outside the army. You do not expect me to draw a comparison between the despair of the two sides to the conflict. If despair exists among the Israelis, that is a good sign. Maybe the despair will bring about public pressure on the leadership to create a new situation.

Do you know what the difference is between a general and a poet? The general counts the number of dead among the enemy on the battlefield, whereas the poet counts how many living people died in the battle. There is no enmity between the dead. There is one enemy: death. The metaphor is clear. The dead on both sides are no longer enemies."

* Could a situation arise in which you would devote yourself to politics, as Vaclav Havel did, for example?

"Havel may have been a good president but he is not known as an exceptional writer. I write poems far better than I practice politics."

* Would you perhaps share with us what you intend to say in the poetry reading event?

"I want to talk about how I went down from the Carmel and how I am now going up and I ask myself why I went down."

* Do you regret having left in 1970, when you were part of a Communist youth delegation, went to Egypt and never returned?

"Sometimes time generates wisdom. History has taught me the meaning of irony. I will always ask the question: Do I regret having left in 1970? I have reached the conclusion that the answer is not important. Maybe the question about why I went down from Mount Carmel is more important."

* Why did you go down?

"In order to return 37 years later. That is to say that I did not go down from the Carmel in 1970 and I did not return in 2007. It is all metaphor. If I am at this moment in Ramallah and next week I am on the Carmel and remember that I have not been there for almost 40 years, the circle is closed and this whole years-long journey will have been a metaphor. Let us not frighten the readers. I do not intend to realize the right of return."

* And if there were a constellation that would enable you to return to the Galilee and Haifa and the family today?

"You were a witness to the powerful emotions when I paid my first visit, in 1996, after an absence of 26 years, and I was supposed to meet with [the late Haifa writer] Emile Habibi as part of a film about his life. I was moved and I also cried and I wanted to stay in Israel. But if you are asking today, I am not ready to exchange my Palestinian ID card for an Israeli one. That would only embarrass me. The relevant criterion today is what I did in those years. I wrote better, I progressed, I developed and I benefited my nation from the literary point of view."

* Some people were critical of the timing by which you chose to read your poems this month, in light of the political situation and the Azmi Bishara affair.

"We are alive, and I do not know what is right and what is not. All our time and our timing are out of joint. This is not my first visit. I was here in 1996 and I delivered a eulogy at Habibi's funeral, and I was here in 2000 and read my poems in Nazareth, and I was at an event of a school I attended in Kafr Yasif. I cannot be part of the disputes between one political party and another. I am a guest of the entire Arab public in Israel and I do not differentiate between the Islamic Movement and Hadash and Balad. I am the poet of them all. Nor should I forget that there are many poets who hate me and there is also hatred among those who consider themselves poets. Envy is a human emotion, but when it turns into hatred that is something else. There are those who view me as a literary menace, but I see them as children who must rebel against their spiritual father. They have the right to kill me, but let them kill me at a high level - in a text."

* Do you have ties with Jewish Israeli intellectuals?

"I am in touch with the poet Yitzhak Laor and with the historian Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin. I have read less Hebrew in the last 20 years, but I am interested in several Israeli writers."

* Do you feel flattered by the fact that seven years ago Yossi Sarid, who was then the minister of education, tried to introduce your poems into the literature curriculum, with the result that some right-wing MKs threatened to dissolve the coalition?

"It is of no interest to me whether my poems are made part of the literature curriculum. When there was a no-confidence motion in the government, I asked mockingly where Israeli pride was - how can you agree to topple a government because of a Palestinian poet, when you have other reasons to do so? Nor is it of interest to me whether my poems are taught in Arab schools. I don't really like being on curricula, because students usually hate the literature that is forced on them."

* Where is home?

"I have no home. I have moved and changed homes so often that I have no home in the deep sense of the word. Home is where I sleep and read and write, and that can be anywhere. I have lived in more than 20 homes already, and I always left behind medicines and books and clothes. I flee."

* In Siham Daoud's archive there are letters, manuscripts and poems that you left behind in 1970.

"I didn't know that I would not return. I thought I would try not to return. It's not that I chose the diaspora freely. For 10 years I was forbidden to leave Haifa, and for three of those years I was under house arrest. I have no special longings for any particular home. After all, a home is not only the objects one has accumulated. A home is a place and a milieu. I have no home.

"Everything looks alike: Ramallah is like Amman and like Paris. Maybe because I was raised on longings, it's not suitable for me to long anymore, and maybe my emotions have gone stale; maybe reason triumphed over emotion and the irony has intensified. I am not the same person."

* Is that why you never established a family?

"My friends remind me occasionally that I was married twice, but I do not remember that in the deep sense. I do not regret not having a child. Maybe he would not have turned out well, maybe he would have been coarse. I don't know why I am apprehensive that he would not have turned out well, but I know clearly that I do not regret it."

* Then what do you regret?

"That I published poems at an early age, and bad poems. I regret having caused damage with words I spoke to a friend or having been coarse and sharp. Maybe I was not faithful to certain memories, but I committed no crime."

* Do you like your loneliness?

"Very much. When I have to attend a dinner, I feel that I am being punished. In recent years I like being alone. I have a need for people when I am in need of them. Tell me, maybe it is selfishness, but I have five to six friends. That is a great many. I have thousands of acquaintances, and that doesn't help."

* Among the poems from your childhood that you find it hard to go back to today, do you include the one about mother's coffee?

"I wrote that poem in Ma'asiyahu Prison in 1963-64. I was invited to read poetry at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and I was then living in Haifa, and I submitted a request [to travel; this was when Israel's Arab population was subject to martial law], but didn't get a reply. I went by train - does that train still exist? The next day I was summoned to the police station in Nazareth and I was sentenced to a suspended sentence of four months and an additional two months in Ma'asiyahu Prison, and it was there, on a yellow pack of Ascot cigarettes with the picture of the camel on it, that I wrote the poem that Lebanese composer Marcel Khalife turned into an anthem. It is considered my most beautiful poem, and I will read it in Haifa."

* Will you visit the village where you were born, Birwa?

"No. Today it is [a kibbutz] called Yas'ur. I prefer to store the memories that still linger of open spaces, fields and watermelons, olive and almond trees. I remember the horse that was tied to the mulberry tree in the yard and how I climbed onto it and was thrown off and got a beating from my mother. She always hit me, because she thought I was a real urchin. I actually don't remember being so mischievous.

"I remember the butterflies and the clear feeling that everything was open. The village stood on a hill and everything was spread out below. One day I was awakened and told that we had to flee. No one said anything about war or danger. We went by foot, I along with my three siblings, to Lebanon, and the youngest was a toddler and never stopped crying the whole way."

* Does your writing oblige a regular ritual, or have you become more flexible with the years?

"There are no conditions, but there are habits. I have become used to writing in the morning between 10 and 12. I write by hand. I do not have a computer and I write only at home and I lock the door even if I am alone in the apartment. I do not disconnect phones. I do not write every day, but I force myself to sit at the desk every day. There is inspiration, maybe there is no inspiration, I don't know. I don't believe all that much in inspiration, but if there is, then one should wait in case it comes when I am not available. Sometimes the best ideas come in places that aren't so nice. In the bathroom, maybe on a plane, sometimes on a train. In Arabic we say 'From the pen of...,' but I think one does not write by hand. Talent lies in one's bottom. You have to know how to sit. If you don't know how to sit, you don't write. Discipline is called for."

* Why do I have the feeling that you don't sleep well?

"I sleep nine hours a night and never have insomnia. I can sleep whenever I want. People say I am spoiled. Where did they say that about me? In the Hebrew press. You say I am considered some sort of prince. A prince is elevated above the people. That is not the case. Nor is it true that I am patronizing. I am shy, and some people construe that as patronizing."

* Does the fact that you touched death at least once in your life make you fear old age and the body's betrayal?

"I encountered death twice, once in 1984 and once in 1998, when I was clinically dead and preparations were already being made for my funeral. In 1984, I had a heart attack in Vienna. That was a deep, easy sleep on a white cloud with clear light. I did not think it was death. I floated and cruised until I felt a powerful pain, and the pain was the signal that I had been returned to life. I was told that I was dead for two minutes.

"In 1998, death was aggressive and violent. It was not a pleasant sleep. I had terrible nightmares. It was not death, it was a painful war. Death itself does not hurt."

* What is your attitude toward death now?

"I am ready for it. I am not waiting for it. I do not like waiting. I have a love poem about the suffering of anticipation. She, the beloved, was late and did not arrive, I said perhaps she went to a place where there is sun. Maybe she went shopping. Maybe she looked in the mirror and fell very much in love with herself and said, It's a pity for someone else to touch me, I am mine. Maybe she had an accident and is now in the hospital. Maybe she called in the morning when I wasn't there because I had gone to buy flowers and a bottle of wine. Maybe she died, because death is like me, doesn't like to wait. I do not like to wait. Death does not like to wait, either.

"I made an agreement with death and made it clear that I am not available for him just yet. I still have things to write, I still have things to do. There is much work and there are wars everywhere, and you, death, have nothing to do with the poetry I write. It's none of your business. But let's set up a meeting. Tell me ahead of time. I will prepare, I will dress up and we will meet in a cafe on the seashore and drink a glass of wine and then you will take me."

* And in life?

"I am not afraid and I am not preoccupied with death. I am ready to accept it when it comes, but let it be brave and knightly, and we will end it all with one blow. Not by methods such as cancer or heart disease or AIDS. Let it not come like a thief. Let it take me in a swoop."

* What makes you a bit happy?

"There is a saying in French that if after the age of 50 you get up without feeling a pain somewhere, you are dead. I am happy to get up every morning. In the broader sense I think that happiness is a not-so- realistic invention. Happiness is a moment. Happiness is a butterfly. I feel happy when I complete a work."

* One gets the feeling that you are more conciliatory than ever.

"This may sound coarse, but that is the aesthetics of despair. I have no illusions. I do not look forward to many things. So if something works out, that is great happiness. There is also humor alongside the despair. I am an 'opsimist' [referring to a play of that name by Emile Habibi]."

* Do you miss Habibi?

"The place would be fuller if Emile Habibi were present. He was a force of nature. He had laughter and he had a special humor and I think he fought against despair by means of humor. He was vanquished in the end. We will all be vanquished, including the victors. One has to know how to behave at the moment of victory and how to behave at the moment of defeat. A society that does not know what defeat is will not become mature."

* Not long ago you completed a new book, a personal journal, a fusion of prose and poetry. Do you actually like yourself?

"Absolutely not. When young poets come to me, and if and when I am capable of giving them advice, I tell them, 'A poet who sits down to write and does not feel like a total cipher will not develop and will not gain recognition.' I feel I have not done anything. That is what pushes me to improve my writing and style and imagery. I feel that I am a cipher, and that means I love myself very much. I have a friend who knows that I can't bear to watch myself appear on television. He told me that this is reverse narcissism. That's what that bastard told me."

Haaretz Magazine,

12/07/2007