IN a leafy neighborhood of this city, where crumbling housing developments give way to gated embassies and idling BMWs, Janet Moore, a high-end travel agent from California, stopped one recent day into the cool, sleek quarters of the Ayyam Gallery on a scouting mission. She wanted to set up studio visits with “the hottest young artists in town,” she told Sharon Othman of the gallery. The plan was to organize a trip for a dozen or so contemporary art collectors, the sort, Ms. Moore said, who, on hearing that Syria is the Next Big Thing, would reach for their checkbooks and head straight for the airport, few questions asked.

“Syria is moving toward a very bright future,” Ms. Othman said, happy to accommodate.

This is one face of Syria now, the one that lately has been making the pages of glossy lifestyle magazines and art-world tip sheets. But just before the travel agent arrived, Ms. Othman had been saying that the gallery couldn’t publish some of its fancy catalogs here, because the nudes in them didn’t pass muster with Syria’s omnipresent censors.

That’s the other face of life here. A corrupt and oppressive regime still rules, and newfound economic prosperity for a well-connected class, while useful as propaganda, has only reinforced a deeper culture of political stagnation.

Stagnant social politics in this part of the world tend to preclude much of an artistic life. That’s the classic historical paradigm. Around here commercial globalization and the Web, having promised to erode the power of authoritarian regimes and foster new cultural riches, mostly have just concentrated more wealth in the hands of those close to power. And, aside from a proliferation of the usual chain stores, boutique hotels and restaurants that are today’s fashionable excuse for “worldly” culture, they have produced among Syrians only a climate of greater unease.

So say many Syrian artists and intellectuals, anyway. Syria’s economic role models used to be East Germany and North Korea. Now the model is China, never mind that Syria has 23 million people, and is about the size of North Dakota. But economic opportunity for the elite clearly hasn’t brought cultural liberalization to the many. If anything, Syrian artists, writers and intellectuals complain that liberties have been only further curtailed by a regime still trying to grasp the challenges of the Web. Every book, art catalog, film script and television program, big or small, still runs a gantlet of government censors. Fifty Syrians can’t congregate in public without getting official consent. When Bashar al-Assad took over as president in 2000, he ushered in a brief period of openness that came to be called the Damascus Spring. But those gains are long gone, and now, despite the influx of first-run Hollywood movies and the token appearance by a pioneering Western dancer or musician for the odd arts festival, the situation has gotten worse.

Why? Perhaps it’s partly a question of changed expectations. Under Mr. Assad’s father, President Hafez al-Assad, there were clear red lines of intolerance. Now those lines are no longer clear, increasing, not diminishing, the sense of uneasiness and tendency toward self-censorship. Rosa Yassin Hassan, a novelist, put it this way one recent morning: “Two people write about the same thing, and one is imprisoned today, the other not. That sends a message, I believe. It is done on purpose to increase fear and apprehension.”

Meanwhile the United States and Western Europe have been making quiet overtures toward Syria, hoping among other things to drive a wedge between it and Iran. Yet Syria has been pursuing its usual wily, paradoxical policies: cracking down on political Islamists at home, supporting movements like Hamas and Hezbollah abroad, accepting new organizations that support women, children and the environment but not human-rights groups that might speak out against the regime. Even as officials allow a few poetry readings, where a small number of Syrians occasionally let off some steam by poking fun at the establishment, they have also drafted a law that would now force bloggers and other journalists to submit all writings for review before publication.

So what culture arises from this climate? For starters, a culture of small-bore opportunism. A young generation of Syrian entrepreneurs, weaned on the Internet and devoted to the global marketplace, has arisen in the last decade or so. They see fresh chances to make big bucks and show little appetite for political confrontation. During the 1960s, and then under Hafez al-Assad in the ’70s, Syria had its version of the youth movement. It survived partly because Syrian activist-artists steeped in Sartre shared with the country’s rulers a dream of pan-Arab prosperity. But today young Syrians, many of them freely admit, dream not about making waves but making money.

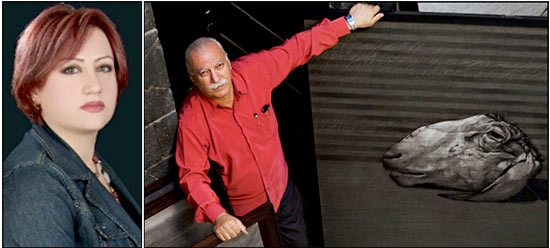

The painter Youssef Abdelke, 59, belongs to an older generation. He moved back here a few years ago, after living 28 years in a kind of self-imposed exile in Paris. His subjects tend to be still lifes, benign seeming at first: fish, birds and other animals, ambiguously dead or alive. “To be dead but to refuse to be dead,” was how he described them when we met in his studio here one evening.

Protest had been part of his upbringing, he recalled. His father had been imprisoned many times during the ’60s and ’70s, he said, and Mr. Abdelke himself, as a young member of the Communist Labor Party, spent nearly two years in prison during the late ’70s. Afterward he moved to France. But he returned in 2005, above all because he missed home and because he is, in the end, a Syrian artist.

“There’s a false image of openness now,” he contended with an openness that was striking but almost casual. “The authorities are still controlling everything, and you can’t even hire a cleaning woman without the security services’ permission. Today the world media knows when a dissident is jailed, which wasn’t the case when I was imprisoned. But this creates an impression that there’s less of a problem, when actually things are just as bad or worse. The market contributes to the problem.”

Syrian artists, exposed to a global audience, “now feel pressure” to cater to nouveau riche Arabs, among others, he said, and they’re less concerned about thorny issues of Syrian identity or Syrian politics.

Mouna Atassi, a veteran dealer whose gallery is one of the finest and most respected in Damascus, echoed that thought, lamenting how the Syrian art world “used to be small but tightly knit.”

“Artists here traded paintings, collectors knew the artists socially,” she said. “They were all middle class. Ambition back then had nothing to do with money. It had to do with ideas.” The last few years have witnessed “tremendous new interest from collectors in the Gulf and in the West and the arrival of big money shaping what people here make and sell,” Ms. Atassi continued. “But it’s all about money and the market now, about tourist consumption and a few rich Syrians.”

Chalk up those remarks by Mr. Abdelke and Ms. Atassi to nostalgia and romanticism. But Ousama Ghanam, a playwright in his 30s who teaches and directs theater here, although describing the situation differently, sounds hardly more optimistic. The problem for serious culture in Syria today, he said, is the lack of money, not the influx of it. He meant that most performing arts events here are still state sponsored. And while the government imposes few “red lines,” in terms of programming, Mr. Ghanam said, the regime naturally favors populist, uncontroversial fare. At the same Syria’s private benefactors, such as they are, so far don’t show much interest in, or just aren’t familiar with experimental theater, dance and film, and they want to back events that make money.

So they’re big on soap operas, perhaps the country’s major artistic export. Mr. Ghanam teaches Robert Wilson, among other modern Western authors and dramatists, to his Syrian students, but he said they graduate only to find that the jobs available as actors, directors and playwrights are all on the soaps. “This is the new reality,” Mr. Ghanam said. “So the soap operas and historical melodramas are creating taste.”

Of course that’s not the whole story. Rosa Yassin Hassan, the young novelist who spoke about the climate of unease, was in a hotel restaurant the other morning, scanning the room for unfriendly faces before settling down to an interview. She noted with resignation a table of aged government officials nearby.

Ms. Hassan has become outspoken here. Syrian censors, she recounted, originally agreed to publish “Ebony,” her first novel, but then excised passages they deemed sexually offensive. When she objected, a public firestorm ensued. Ms. Hassan decided to publish abroad. Her next book chronicled the lives of former female political prisoners. The book after that landed her on the shortlist for an Arabic version of the Booker Prize but stirred more condemnation, and today Ms. Hassan isn’t allowed travel outside the country.

“It’s complicated,” she said, about the situation, “because nowadays, with the Internet and satellite TV and translations from and to Arabic, writers in Syria are not isolated from the world. It is not like it was 30 years ago. We can publish elsewhere. There can be a public fuss. But in a sense this only makes the situation feel worse for younger writers because we can dream.”

The Syrian reading public, she went on, “has always been tiny, and intellectuals are isolated from the rest of society.” At the same time a young literary scene has developed, she insisted, publishing abroad, like herself, if necessary, and writing about issues like “social diversity, life among refugees and minorities, subjects that used to be unexplored.”

“It’s more about individual expression now, which to me is in the best long-term interest of culture as culture,” she said, adding that making art in Syria is “like dropping a pebble in still water.”

That happened to be the metaphor Hatem Ali also used. At 48, Mr. Ali is one of Syria’s most successful television and film directors. He has directed several of the country’s widely distributed historical soap operas, and he recently shot a feature film, “The Long Night,” about political prisoners. We met in his office suite here one morning, beneath a photograph of Mr. Ali standing beside President Assad.

The soaps bought him, as he put it, “immunity” to make “The Long Night.” He was able to muster $250,000 in private money, a meager budget. The film was then tacitly banned by Syrian authorities, who never gave permission for it to be shown here. “We got permission on paper from one committee to go ahead with the film, but then another government committee saw the film, and my own long night with the Syrian authorities started,” he said, shaking his head.

So why did he make it?

“Young Syrian directors who grew up with the success of Syrian dramas see television as where the money and opportunities are now, and they produce shows that long for a backward world and that hide in religion and the historical past, no matter how bad the past was,” he said.

I had seen what he meant just the previous night, wandering past a cafe where dozens of Syrians had gathered outdoors as usual to watch, on a big screen, “Bab al-Hara,” a hugely popular soap opera across the Arab world about life in Damascus at the turn of the last century. In it women gossip, men shoot guns and shout at one another. It’s what passes for popular culture — not worse than what passes for it in Rome or Red Hook, maybe, except that for Syrians the alternatives are few.

“It’s our job to raise our voices, a little bit,” Mr. Ali said, speaking about Syrian artists generally. “Movies don’t move people to revolution. But they’re part of a discourse, pebbles in a still lake.”

“I am not desperate yet,” he added. “But I am less hopeful.”

http://www.nytimes.com